Why brilliant research fails to land, and what to do about it

Daniel Haight

Dec 9, 2025

Fourteen percent of research makes it into practice. The other eighty-six percent is cited, celebrated, and ignored. And if you're in the lucky fourteen percent, you'll still wait an average of seventeen years.

Seventeen years. That's longer than many academic careers. Long enough for the graduate student who ran the analysis to become the department chair who ignores it.

These numbers come from medicine, where they actually track this sort of thing. In policy research, we don't measure as carefully. Probably for the best. The denominators would be embarrassing.

And here's what makes it worse: those studies were conducted when people still trusted institutions. The intermediaries who used to translate research for broader audiences have either lost credibility or lost funding. Your local paper laid off its statehouse reporter in 2014. Nobody's finding your local angle for you.

You can no longer borrow trust. You have to build it yourself.

The problem is that most research communication is built for a pulpit. You stand up, preach your findings, and hope someone in the congregation is listening. Press release, PDF, conference keynote. One message, broadcast outward. If it doesn't land, you try again.

Interactive data visualization (IDV) works differently. It's a sandbox, not a pulpit. A tool that lets your audience explore your data, test your model against what they already know, and find their own stake in what you've discovered.

Here's why that works.

The Three Questions

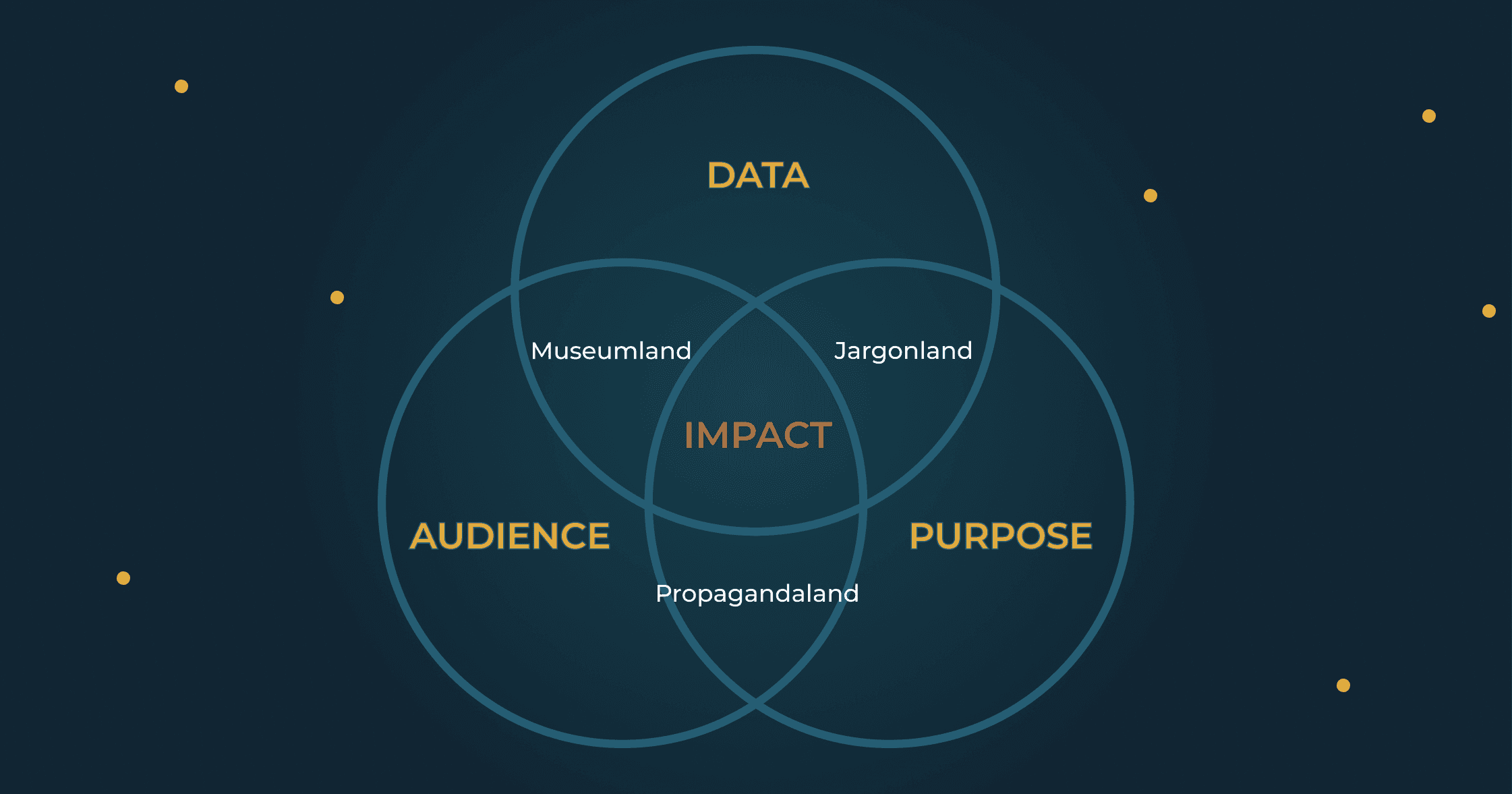

Every audience is silently asking three questions. They won't articulate them. They might not even know they're asking. But their willingness to act depends on how you answer.

Question One: Can I see it?

This is the understanding question. Can they picture what you're describing? Or is your methodology a black box? If your jargon is a foreign language, then they're nodding politely while writing a grocery list in their heads.

Most researchers recognize this one. It's why we build explainers and reach for metaphors.

Question Two: Can I check it?

This is the verification question. They understand you perfectly. They just don't believe you. Maybe they've been burned by research that turned out to be advocacy in a lab coat. Maybe they watched eggs go from staple to poison to superfood in a single generation and decided "studies show" is a punchline, not a credential.

You used to clear this question by borrowing credibility from your institution, your journal, your funder. That path is narrowing. Trust now has to be earned one interaction at a time.

Question Three: Is it mine?

This is the ownership question. They understand. They believe. They don't care. You gave them a national finding when they needed their county. A policy implication when they needed a headline. A methodology section when they needed something they could use on Tuesday morning.

The pulpit forces you to pick one question to optimize, for one audience, and hope for the best. A sandbox answers all three.

How It Works in Practice

Most communication formats answer one question well and hope the others take care of themselves. The best interactive tools answer all three in sequence. Here's what that looks like.

Fifteen years ago, we built a tool that predicted teacher shortages. County by county, ten years into the future. The model was textbook demography: cohort components, retirement curves, birth rates, migration patterns. The kind of methodology that makes academics nod approvingly and school board members check their phones.

So we added an animated explainer. Sixty seconds showing how the pieces fit together. People age. They move. They have kids. Kids need teachers. We figured users would watch the explainer, then check their county's forecast.

They didn't.

A superintendent from a rural district spent her first ten minutes everywhere but home. She found the beach counties and watched seasonal workers flood in every summer, drain away by September. She poked at the oil patch and saw families arrive during boom years and then vanish when prices crashed. She checked the college towns and spotted the predictable spike of eighteen-year-olds every spring, most gone by twenty-one.

Only then did she navigate to her own county. And by then, something had shifted. She wasn't skeptical anymore. She wasn't confused. When she saw the impending influx of kindergartners, she was ready to act.

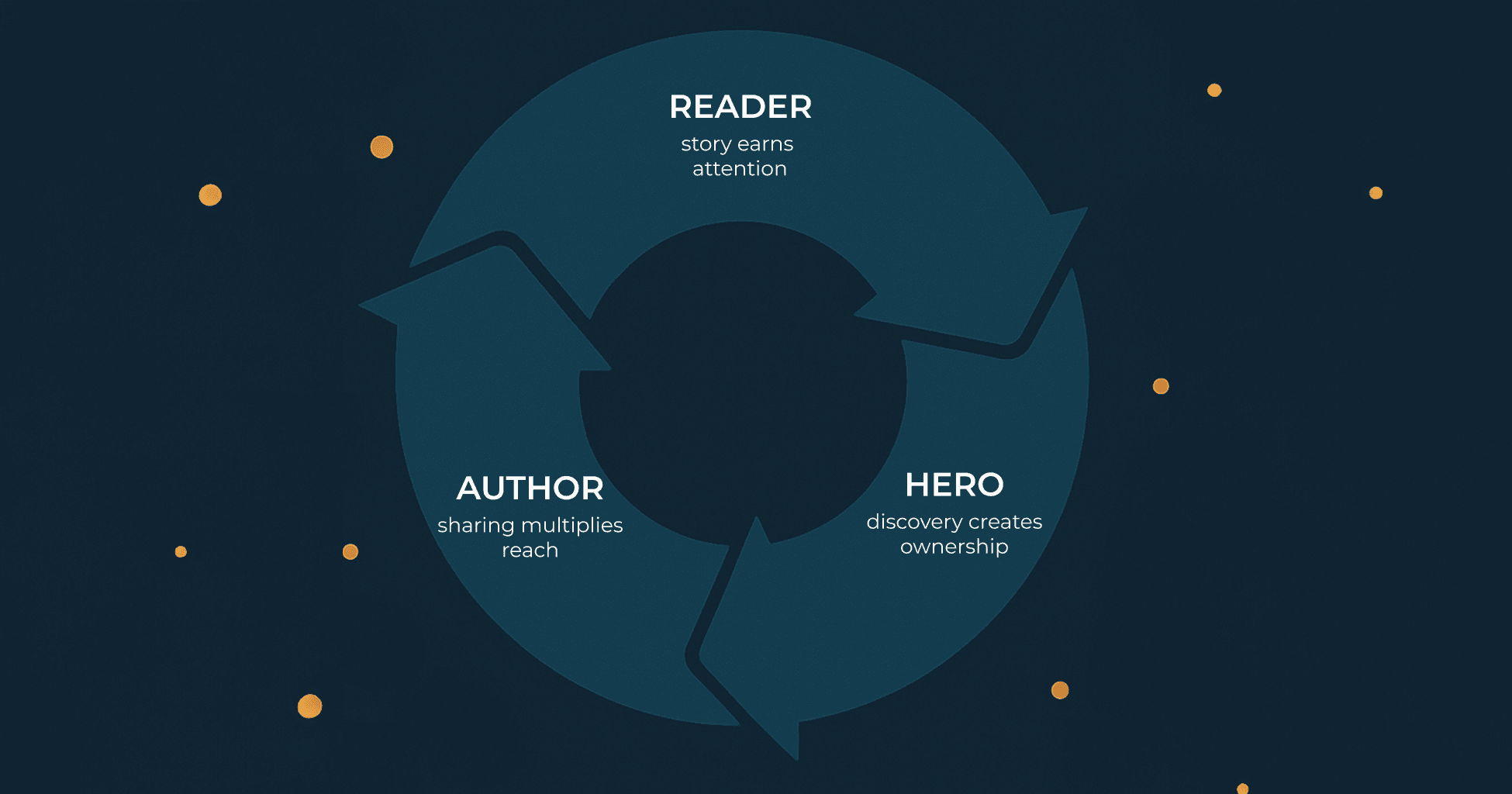

We've seen this pattern hundreds of times since: understanding, then verification, then ownership. First they get the concept. Then they test it against what they already know. Then they find their own stake.

Three questions. One session. All answered.

The Sandbox Principle

Trust is not transferred. It's earned. And it's earned through constrained exploration.

When we build an interactive data visualization, we're not building dashboards (which display conclusions) or open databases (which overwhelm with possibility). We're building sandboxes: bounded spaces where users can test our models against their own knowledge.

The boundaries matter as much as the space inside. A sandbox without edges is a desert. Users wander, lose orientation, abandon the effort. A sandbox too small is a display case. Users look but can't touch, and looking isn't enough to create belief.

The right sandbox lets them find something familiar (a place they know, a variable they understand), test your model against it (does it match their experience?), build confidence through verification (the model passed their test), and locate themselves (now they'll look for their own stake).

The sandbox is where skeptics become believers. Not because you argued them into it, but because they argued themselves into it.

Why This Works

Psychologists call it the "generation effect." Information we generate ourselves, through exploration and discovery, sticks far better than information we simply read. When the superintendent discovered that oil towns boom and bust, that insight became hers. Not because we told her. Because she found it.

Discovery creates ownership. Ownership creates conviction.

Broadcast delivers findings. Interactive visualization lets people discover them. That's not a stylistic preference. It's a different cognitive process entirely.

The Path Forward

Seventeen years and fourteen percent isn't destiny. It's the cost of a communication architecture designed for borrowed trust, institutional translation, and one-size-fits-all messaging.

That world ended. The question is whether your research communication has caught up.

And yes, I recognize the irony: I've just written an article arguing that articles don't change minds. If you've read this far, you've proven the point. You were already looking. You just needed language for what you suspected.

Now go build something people can discover for themselves.

More From the Blog

LOVE DATA AS MUCH AS WE DO?

Join our readers who get design tips, visualization stories, and clarity straight from Darkhorse.